Hi friends,

This past week marks twenty years since the UK and US invaded Iraq. I am now thirty years old, just a little bit younger than my parents were when they decided to take their young family on a march against the war. That London-based demonstration was part of a coordinated global day of action against invasion and is now considered the largest protest event in human history.

With this in mind, today’s Murmuration offers my childhood recollection of the day, and asks: what was the point in that?

We were living in a village called Hasland in Derbyshire; my Saturday morning was usually spent in ballet class at Rita Owen’s Dance School, which I loved. My Dad is a Methodist Minister and so his Saturday’s were normally spent writing sermons, or drinking tea at a coffee morning. But on this Saturday, February 15th 2003, my parent’s woke me and my younger sister up whilst it was still dark and drove us to the local council offices. From there we boarded one of six coaches taking protestors from Chesterfield to central London.

In the process of writing today’s Murmuration I have spoken to my parents to try and pin them down on some details: how did they hear about the fact that transport was being put on? ‘Coaches were organised by the Stop the War Coalition’ my Mum remembers, ‘I think I must have read about it in the newspaper. We also had the internet by then, so it could have been an internet thing, I guess.’

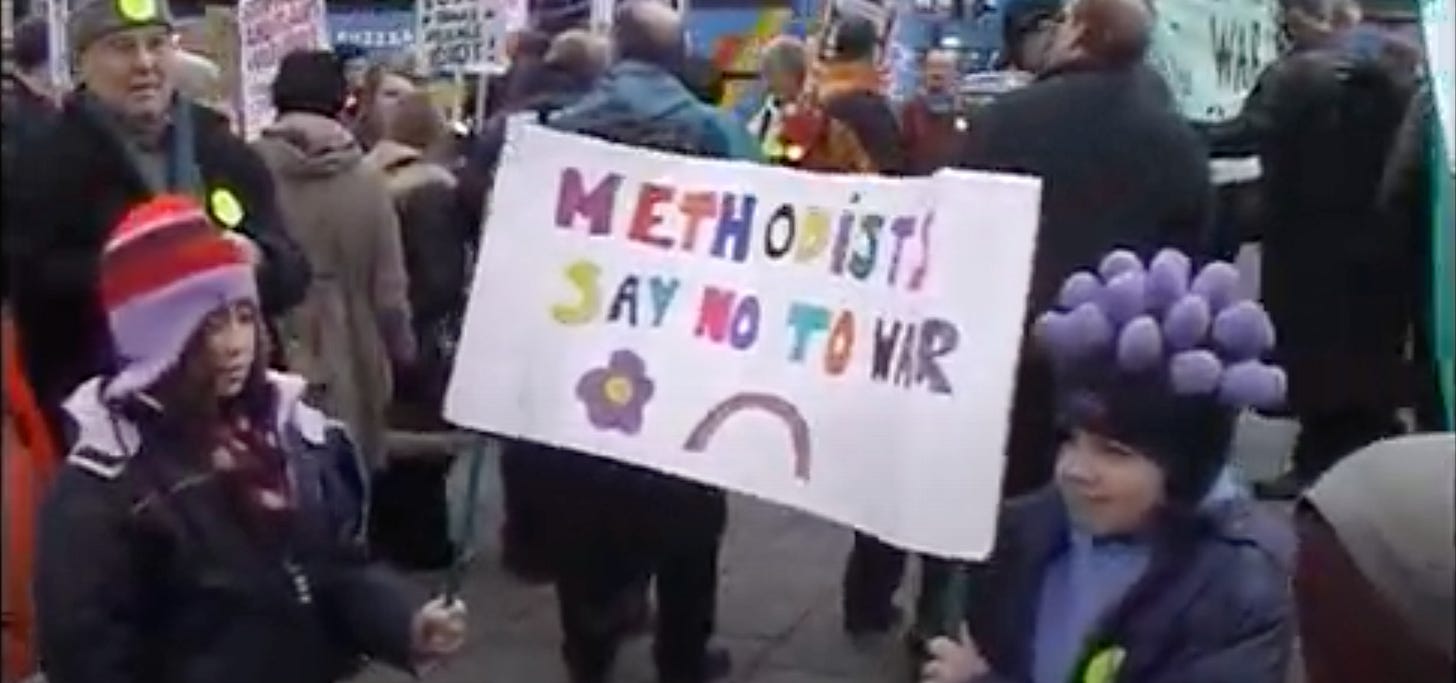

The night before the march we got out our felt tips and made a banner, adorning it with rainbows and flowers. Two pieces of green garden dowel were attached to either side for a bit more height. Our banner said ‘Methodists Say No to War’, but perhaps it could have said: ‘This family, and the family of Christ, says no to war’.

Reading this, you might assume that I grew up in a Political Family, and that going on protests was a normal thing for us to do. Well, I did grow up in a political family, but I would argue that it was this moment that turned us into one. Up until the time of the invasion my parents had never taken us on any marches or demonstrations, and were not affiliated with any political parties or pressure groups. They had both grown up in families where small-c christian conservatism would have been the norm. I’ve come to believe that the march served as a catalyst for my parent’s nascent political consciousness, and also had a profound impact on their two children.

I’m not sure if my memories of the day are actual memories, or just recollections I’ve internalised by osmosis from our home-footage. But I seem to recall that we walked alongside other people of faith, Quakers and Muslims, and that most of the people around us were a fair bit older than my parents.

‘There were babes in prams, there were people in wheelchairs, and there were elderly people, all wanting their voice to be heard’

There were huge demagogic incarnations of Bush and Blair held aloft our heads, banners that identified them as war criminals and images of both leaders covered in blood.

It was cold, really cold. Partly because we weren’t moving very quickly. My parents bought Jaffa cakes and a Crunch bar to keep our energy levels up. As we walked down the Mall someone had propped their speakers up on the window ledge and played All You Need Is Love to the masses below.

My young parents were using the promise of a ‘big performance’ at Hyde Park to lure their two girls along the route. I had to look up exactly who gave speeches at the ‘performance’ and was a little bemused to see Harold Pinter, George Galloway, Tony Benn and Bianca Jagger on the roster—not exactly names that would win over any seven and ten year old I know.

If you watch the footage it becomes clear that we didn’t actually make it to Hyde Park or the ‘big performance’ as intended: ‘The body of people had been so large that it took us five and half hours to complete the march. We never heard a speech … we marched from one side of London to the other, and then hopped back on the bus and came back home again.’

And that’s what we did. We went back to our home in Chesterfield, back to our school and back to church. I’m sure I would have told my classmates about my weekend excursion, but beyond that, it would have been difficult to put into words quite what we had been part of that weekend.

Because on the face of it the largest protest event in human history was a failure. Just one month later, on March 20th, the UK & US launched their invasion, predicated on the presence of ‘weapons of mass destruction’ which were never found. According to Iraq Body Count 200,000 civilians and 100,000 combatants were violently killed as a consequence of the conflict.

This week I listened to Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart reflect on their involvement in the Iraq war. Aged thirty, Rory Stewart was working for the Foreign Office, and was one of the first diplomats to arrive in the war-torn country. There he was swiftly installed as a ‘governor’ of the southern Iraq region, where he was responsible for a population of one million restless Iraqis, many of whom were deeply unhappy about the occupation’s presence in the region. During the podcast Stewart recalled the unhappiness he felt at this time, saying that even by September 2003, just six months after the war began, it was clear that the ‘transition’ was going pear-shaped, a failure.

And so what is there left to say about this unhappy period of our history? Of the Iraqi people’s history? There’s no doubt that the failure of Iraq changed British foreign policy and the way neoliberal interventionism was viewed. By the time it came to the war in Syria any form of military intervention was politically untenable. The UK chose not to intervene there, creating a vacuum in which the likes of Russia could intercede.

The British Invasion of Iraq had other consequences. It turned the likes of Blair and Campbell into political pariahs, and indelibly wedded Labour’s political identity to a potentially illegal war. It also served as a stark reminder of Britain’s shrinking presence on the world stage. In The Rest in Politics podcast Alastair Campbell admitted that our role there was largely one of ‘tinkering at the edges’ whilst the US made the big calls about the nature of the transition.

When we describe this moment in history, putting numbers to the lives lost and tracing the wars intractable impact, it can feel like we went on the march against the war for nothing. The politicians didn’t listen to us. The Iraqi people suffered immeasurably, and continue to do so.

But on a human level, I know going on that march transformed my family. It shaped our collective understanding of solidarity, and what it meant to speak truth to power. The fact that we were ostensibly ignored on that occasion mattered, of course it did, but it also revealed the power of protest as a creative act in our lives. Protest is always an act of the imagination, a way of saying: it doesn’t have to be like this.

The Indian writer and author Arundhati Roy has said that: ‘Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. Maybe many of us won’t be able to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.’

My parents remain politically active, protesting against climate inaction and organising on matters like divestment within the church. Their daughters both went on to study politics, and continue to join them on protests. I’m sure it won’t be long before their granddaughter joins them too.

‘I don’t think anyone regretted the time and energy that they’d invested in that day. It was a time for making your voice heard, when you feel that no-one else is listening.'

Thank you for reading,

I’d love to hear about your experiences of protest and the impact it has had on your life. Let me know in the comments.

Grace

Share this post