As I see it, one of the primary tasks of the writer is to observe the connections between things. Extraordinary things, ordinary things, and awful things. How might an event that took place 100 years ago still affect people in the present, asks one novelist? What does the allocation of domestic work say about the way we relate to each other as humans, opines another? And how do the day-to-day decisions I take affect the lives of people I may never meet?

It is the search for connection between things which drives so many of us to put pen to paper and engage in an artistic practice. We are aware that our lives are bound up with each other in ways that are both unremarkable and deeply mysterious, and we attempt to put that feeling into words. In this respect, every creative act is an attempt to say: this is what I see happening in our world, do you see it too?

This week the Edinburgh International Book Festival announced ‘with regret’ that it would be ending it’s relationship with the investment management fund Baillie Gifford. This decision followed calls from the Fossil Free Books campaign for the fund to divest from companies that ‘profit from fossil fuels and Israeli occupation, apartheid and genocide.’ As a book industry worker, I am a member of the Fossil Free Books campaign, whose members employ tactics such as boycotting major literary festivals. To date, the campaign has been highly effective, with both Edinburgh and Hay festival dropping links with BG following author boycotts.

In their press release, the EIBF and Baillie heaped criticism on the FFB campaign, arguing that ‘Undermining the long-term future of charitable organisations such as book festivals is not the right way to bring about change.’ They characterised FFB as an anonymous, aggressive and puritanical group (hello there!) which is piling pressure on authors to pull out of festivals. The general argument against our approach is that it’s short sighted and will put our wonderful book festivals out of business in a time when arts funding is already in peril.

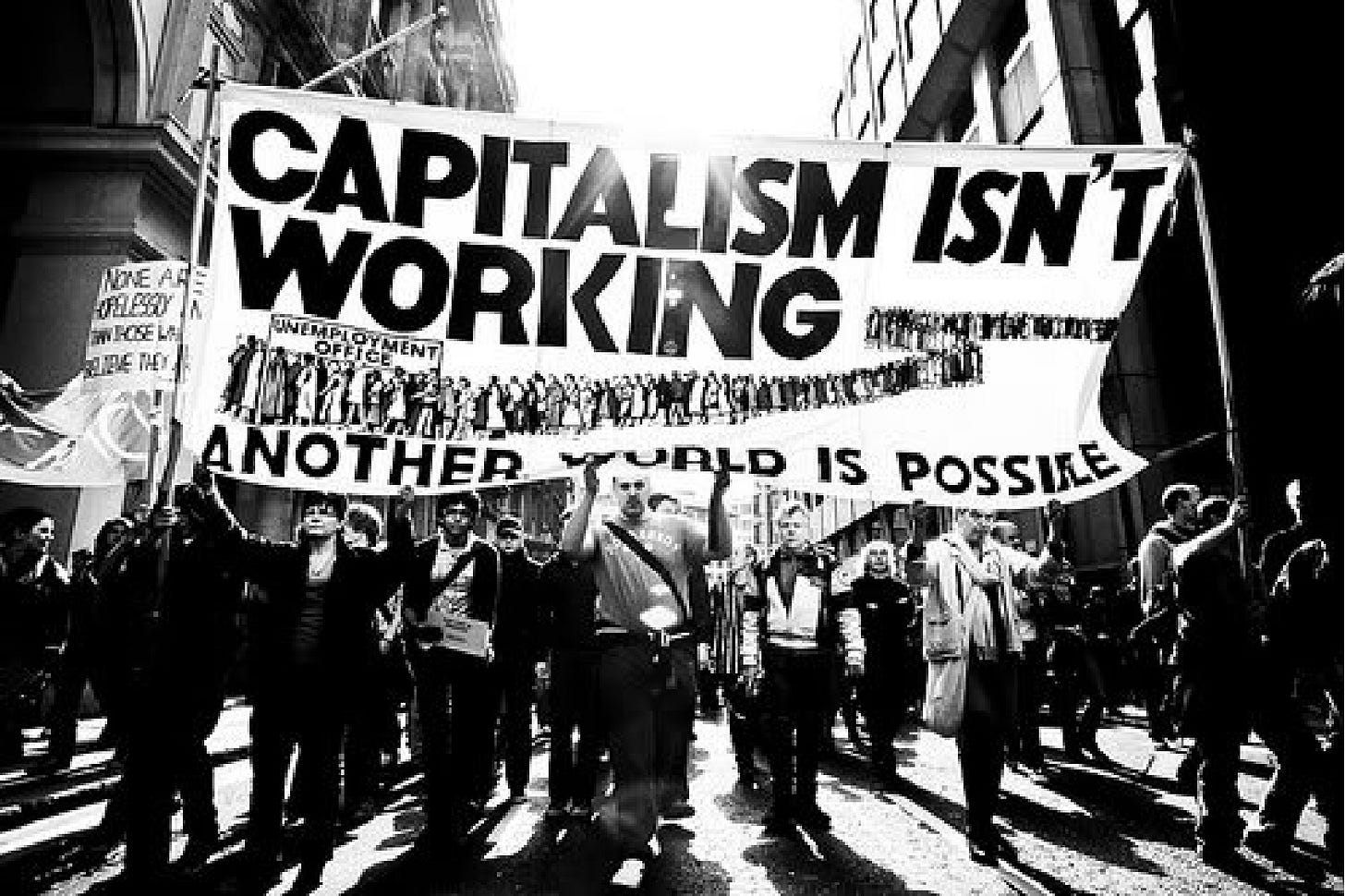

It comes as no surprise to me that instead of willingly divesting, the forces of capitalism choose to blame a nascent campaign organised by low-wage workers for the collapse of arts funding in the UK. Baillie Gifford seems intent on eeking out the financial benefit from their investments for as long as possible. As someone involved in previous divestment campaigns, their response does not surprise me. But the broader idea implicit in EIBF’s response- that in order to be viable the arts sector must depend on money raised (in part) from the desecration of our environment and an illegal occupation- shows an utter failure of the sector’s collective imagination. Perhaps more significantly, it is a failure to recognise the inherent role culture plays in identifying connections between our choices and the impact they have on the world.

It may shock you to hear that investment firms are not renowned for using their imaginations in the same way writers do. They look instead to the norms and trends of markets and the safety of their spreadsheets. This is why non-violent acts, such as with the withdrawal of labour, work as effective way of signalling a cultural norm-shift to the market. The logic is that as norms in culture and the market change, so too will the make-up of their portfolios. And because investment companies tend to uphold the status quo rather than transgress it voluntarily, shifts in culture play a crucial role in shaping their behaviour.

Perhaps perversely, I took some comfort in the venom directed at our campaign by EIBF and Baillie Gifford this week. Their attack is a sign that the FFB campaign is working, and that the norms that have dictated funding arrangements for literary festivals for decades are shifting. During a time of genocide and climate collapse, actively choosing to invest in companies which facilitate these phenomena is becoming an ethically untenable position. ‘After the final no there is a yes’ wrote Wallace Stevens', ‘and on that yes the future of the world hangs.’ Although it wasn’t portrayed that way, this week we saw a ‘no’ become a ‘yes’.

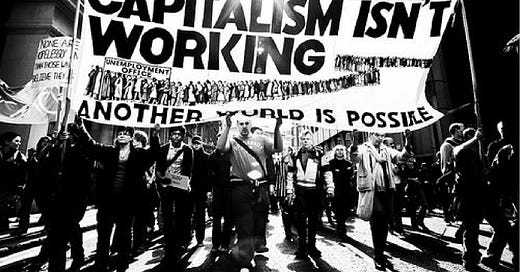

Capitalism says that we must choose between a viable arts sector and a fossil-free world. I believe this is a false binary, and effectively a way in which fossil fuel and Israeli interests are trying to cling on to cultural influence in a world that is in rapid transition. But a different world is possible, and already on her way.

‘Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction’ writes Walidah Imarisha, ‘We want organizers and movement builders to be able to claim the vast space of possibility, to be birthing visionary stories.’ I am not a hedge-fund manager, but I am a writer, and I believe that part of my job is to articulate a vision of the world not just as it is, but as it shall be when our inherent connectedness to each other is fully recognised.

Grace Pengelly is a writer and editor, and member of the Fossil Free Books campaign. This essay was written in a personal capacity.

Quite galling this week to see so many arts/culture people and other literary festivals (including my local one) defend BG more than a movement that seeks to end reliance on dodgy (to put it lightly) funding. And the irony too, of the total absence of creativity in imagining alternative futures!

Utterly inspiring, loved this part:

"It may shock you to hear that investment firms are not renowned for using their imaginations in the same way writers do."

Thank you for sharing these thoughts, Grace.