During a particularly difficult period of my life, in which I did not understand who I really was nor where my days were taking me, I had a poem by Ellen Bass sellotaped to my computer’s monitor screen. It opens like this:

The Thing Is

to love life, to love it even

when you have no stomach for it

and everything you’ve held dear

crumbles like burnt paper in your hands,

your throat filled with the silt of it.

As my life seemed to unspool, and I could taste it’s ashiness on my tongue, I would read and reread these words like a mantra, willing them to be true. In these months, it was life itself—the state of being alive—which seemed to be the active source of my pain. I found all aspects of day-to-day life difficult; waking up, relationships, work, and my feelings about myself all emerged from a place of deep sadness and anxiousness. I don’t think I was suicidal, but I found most moments of my day difficult to endure and only found respite in the company of a woman who would let me sit in silence with her. She would occasionally ask me question, to see if I could connect to any other feelings or senses beyond my depression. Sometimes I would explain that for a moment that day I had felt a sense of peace. She would ask me to focus on that sensation, if I could, and observe that feeling peace was a possibility for me.

In The Thing Is, Ellen paints a tender portrait of this process. Specifically how we might learn to access love once more. Not through sheer will or brute force, but through the gentle repositioning of our stance towards it. When we experience so much pain that we question ‘How can a body withstand this?’ she suggests not denying the fact of our pain, but instead telling your life that you ‘will’ love it, again:

Then you hold life like a face

between your palms, a plain face,

no charming smile, no violet eyes,

and you say, yes, I will take you

I will love you, again.

In this image, Bass seems to suggest that we can subtly and incrementally adjust the posture of our soul towards life rather than death. This possibility, that we will love life again in the future, then becomes the lifeline by which we are able to make it through the ‘tropical heat’ of our grief.

Whilst Ellen’s poem has often spoken to me in times of depression, at the moment I find myself returning to her words with the collective in mind. I see people asking how do we love this world amidst all this horror? Or How should I live when so many face a brutal existence? These are important and understandable questions, but it is worth acknowledging that we are far from the first people to have asked them.

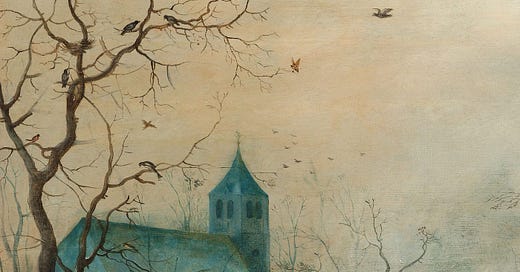

Writing in her diary during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1941, a young Dutch Jew called Etty Hillesum described going for a walk around a skating club in Amsterdam on two different occasions. Of the first she wrote how witnessing the ‘soft hues in the sky … trees alive with the light through the tracery of their branches’ would have once ‘gone like a stab to my heart, and I would not have known what to do with the pain.’ But on the second occasion she explained that she ‘reacted quite differently. I felt that God’s world was beautiful despite everything, but its beauty now filled me with joy.’ Hillesum’s exquisite and radically honest diaries chronicle an inner spiritual journey, but also describe her detention in Westerbrook and Auschwitz concentration camps, where she was murdered at the age of 29. She, more than any other writer I’m aware of, seems to have understood what it means to access and draw on the possibility of love when all else ‘crumbles like burnt paper in your hands.’

Writing to a friend about her experience in Westerbrook she says:

The misery here is quite terrible; and yet, late at night when the day has slunk away into the depths behind me, I often walk with a spring in my step along the barbed wire. … Like some elementary force - the feeling that life is glorious and magnificent, and that one day we shall be building a whole new world. Against every new outrage and every fresh horror, we shall put up one more piece of love and goodness, drawing strength from within ourselves.

If you are reading this then I pray you will never be subjected to the horrors that Etty Hillesum faced in her lifetime. But that does not diminish how painful it is to watch mass-murder unfurl, seemingly unfettered, in Gaza. To hear the delight with which trans-rights are being eroded in the UK. Or to listen to reports of death and disaster in the DRC. It is awful to bear witness to the worst of our world. But I would argue that it is precisely because of these events that we must protect our hearts against the darkness and hatred which seeks to overpower us all. Instead, ‘we shall put up one more piece of love and goodness.’ And if we can’t manage that, then we shall train our attention on the possibility of love. One small step at a time.

I needed that too - thank you

Thank you Grace, in the deep place within (when there are no words, only awareness of each moment) the connection I feel, as I read, is profound.

&