Dear friends,

Welcome to another edition of The Murmuration. This week we’re diving into all things postpartum. If you are a man who perhaps thinks ‘birth stuff’ doesn’t apply to you, then I implore you to read on and understand why it does.

Some housekeeping:

Thank you to everyone who got in touch after my last newsletter ‘in which I stop trying to be good’. I can’t tell you how much it has meant to have your support as I brave this new freelance world.

Substack has just launched a new Notes feature, which is like Twitter but without the bots and fascists. Come and hang out with me there, if you like.

In twelve days my daughter turns one. To celebrate her first birthday both sets of grandparents will travel to our home in Somerset (no doubt laden with gifts), and I will attempt to bake a cake. My daughter will also wear a special birthday crown.

It will have been 365 days since I gave birth, and nine months since I was diagnosed with postpartum depression. My daughter will have been crawling for six months, and sleeping in her own cot for seven.

I state these numbers and figures not in a mournful way, but to highlight the extent to which time and its measurement becomes an instrumental part of a mother’s life, both before and after the birth of her child.

In utero, the growth and development of a foetus is narrated by a series of apps, which remind parents that their baby is now the size of a kiwi, or a medium-sized butternut squash. Friends of mine referred to their daughter as ‘sesame’ for the first few weeks of her life. After birth, midwives and doctors fastidiously monitor a child’s health according to days, then weeks and months. On Day Three I remember being paranoid about the fact that my baby didn’t appear interested in my milk. By Day Seven a midwife declared that she was feeding ‘normally’(whatever that means), and that I wasn’t to worry.

For good and for ill, a baby’s life post-birth is broken down into quantifiable milestones which are observed with care and adoration by a whole host of parties.

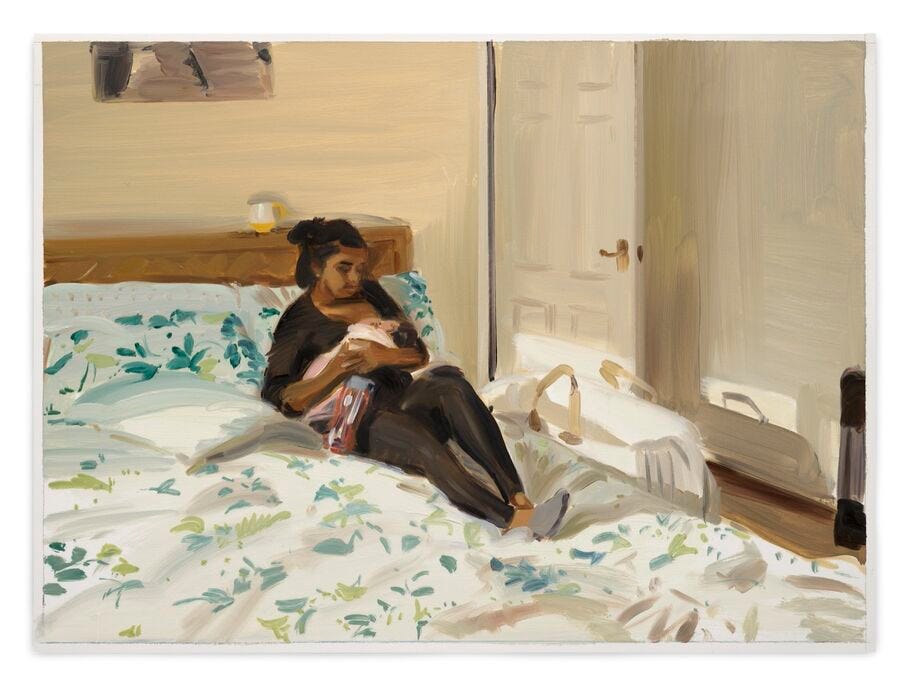

For mothers the time following the birth of a child is referred to as the ‘postpartum’ period. During this time new mothers are responsible for helping their newborns meet these aforementioned goals, whilst also recovering from a major medical, emotional and (whisper it) spiritual event.

As for how long postpartum lasts, well, that appears totally up for grabs and dependent on the culture that you are raising your child within. In China, the ancient tradition of zuo yue zi (translated as: sitting a moon cycle) remains a popular practice for mothers. It requires a physical convalescence for a period of a month. In Korea, saam chim ill is a three-week period of convalescence involving lots of seaweed soup. In some Indian communities new mothers may return to their childhood home for up to three months.

In the UK there are some subtle shifts occurring around our perception of the postpartum period. But usage of the term remains closely tied to medical treatment. If the birth took place in a hospital then it is not uncommon to be discharged within twenty-four hours, (or at least as soon as a woman can prove that her bladder still functions). Following discharge into the community, a midwife will carry out home visits, checking on the health of parent and child, and the final routine checkup occurs six weeks postpartum. Over the next few weeks friends might organise food deliveries and family might help with the housework, but this is not formalised like it is in other cultures and many new parents find themselves without extra support.

The medical window in which a British woman is viewed and cared for as postpartum is narrow. And societally too, the emphasis is often skewed as to how quickly mothers can get back to their ‘normal’ selves. ‘You’ll soon feel back to normal’ new mothers are told, as they struggle to navigate their career alongside their newfound caring responsibilities.

Outside of a medically sanctioned spell of about three months, we are culturally conditioned to ameliorate the fact that we gave birth and to downplay the extent to which our lives are fundamentally altered as a consequence. Those who dare to speak frankly and honestly about their postpartum life have historically found themselves castigated, as the author Rachel Cusk did when she first published her her aptly titled memoir ‘A Life’s Work’:

Time hangs heavy on us and I find that I am waiting, waiting for her days to pass, trying to meet the bare qualification of life which is for her to have existed in time. In this lonely place I am indeed not free: the kitchen is a cell, a place of no possibility. I have given up my membership of the world I used to live in.

Cusk here identifies the way in which giving birth and becoming a parent alters our experience of time and reality. These two experiences combine to rupture our very sense of how long days and weeks and months are. Time ‘hangs heavy’ and also vanishes. In a deeply mysterious sense, the people we were before we gave birth also cease to exist.

It can sound almost trite to say that giving birth changes your life. As soon as we try to articulate our experience our observations suddenly seem quite banal, as if we lack the language needed to articulate the seismic transformation we are undergoing.

In her excellent forthcoming book ‘Natality’, the author and publisher Jennifer Banks is critical of the wholly insufficient amount of attention given to birth from both the academy and culture writ-large. Birth, she argues, has been presented as a ‘singular event, a succinct and contained vignette’ and has always lacked a clear definition. It strikes me that if postpartum (a latin translation meaning post-birth) is an idea that has been downplayed and compartmentalised in western culture, then it’s the ideas we hold about birth itself which have laid the groundwork.

Turning to the work of the political philosopher Hannah Arendt, Banks identifies an almost overlooked idea in her writings - that of ‘natality’, as a concept that might be able to offer a more robust and illuminating perspective on the role of birth and it’s aftermath in all of our lives. For Arendt natality is:

“the supreme capacity of man” the “miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, ‘natural’ ruin.”

Banks explains the concept in more straightforward terms: ‘because we all were born … we are always all capable of beginning again, of starting something new through each human action.’ Birth, in addition to the physical act of labour, is therefore about an engagement with the world and all that entails at any given moment of history. It is also the inherently creative act which ‘guarantees us the ability to act, to work as agents in our societies.’

Perhaps surprisingly, given the context during which Arendt was writing, this more optimistic interpretation of birth stands in rather stark contrast to the bleak and individualised account of new motherhood offered to us by Rachel Cusk. For Arendt, who never had children and was exposed to the height of Nazi fascism, birth was diametrically opposite to totalitarianism. ‘“Ideologies” she wrote “are never interested in the miracle of being.”’ For Arendt, birth was always concerned with future potential, the idea that we (as a species) can make and remake ourselves, and in so doing, remake our relationships to each other.

For Banks, the concept of Natality seems to offer a more neutral space from which to reflect on the relationship between a life and its relationship to the world. ‘Natality requires a zeroing in on birth but also a zooming out, an exploration of birth’s aftermath and the larger shape a human life takes.’ Natality broadens our understanding of birth, taking a more anthropological & holistic view of the impact that birth has upon us at a species-wide, societal and planetary level.

Could postpartum be reframed in a similar way? Instead of understanding it as a narrow three month period after birth, could we acknowledge the ways in which we all live in a time after birth, which is an opportunity for us to refashion our relationship to ourselves and the environment which enabled us to come into being? What if we treated each other in the way a new mother would (secretly) like to be treated; with sensitively and generosity? What if we treated our planet to a period of convalescence and seaweed soup?

Over the past five years or so I have had the deep privilege of walking alongside many first time mothers as we collectively navigate the new terrain of postpartum life. One of my fellow mothers-in-arms, Kerri ní Dochartaigh, has written about this transition in the most wise and thoughtful terms on her own newsletter Scéal.

She writes that:

motherhood has made clear to me in ways that nothing did before, just what it means to be a woman in a world like this one … It matters to me that I raise a son who knows, respects and loves himself and every being he shares the earth with.

Kerri possesses a deep sense of natality, and understands instinctively that to be a mother to a small child is to mother the potential of a whole world. In this sense, motherhood may be an avenue towards understanding our own ancestral traumas and becomes ‘the miracle which saves the world’.

Part of me wonders if I truly believe this. After all, someone was a mother to Hitler, and Putin, and all the other unpleasant people who have wreaked havoc on our world. Perhaps this is why Jennifer Banks chose to look at natality through the lives of such a varied cast of thinkers, including Arendt, Nitzsche and Toni Morrison, who were writing during the darkest periods of recent history, and yet were somehow able to recognise the essential role natality plays in overcoming these political and societal scars.

Similarly, Banks does not seek to minimise or dismiss the trauma, ‘unresolved problems’ and injustices experienced by women at an individual level, but tries to highlight how humanity’s ongoing commitment to creating new life is ‘implicated in the transformation of human civilisation.’

We are all post-birth, and for those who have given birth, the postpartum experience is a never-ending one, which compels us to approach daily life in light of this remarkable and transformative event. Freed from its narrow, western time constraints, a postpartum view of the world could be one which prioritises individual and societal healing, respect for environmental and planetary boundaries, and invites us to participate in the ongoing co-creation of the world.

I’M LISTENING TO:

Heart Full of Love by Cleo Sol

‘Sol is mothered, and mothering.’ writes the Guardian of her second studio album. Heavenly!

I’M READING:

Natality: Towards a Philosophy of Birth by Jennifer Banks

A bold and illuminating book on the matter of birth (which is really the matter of life itself). It publishes in the US in May. British publishers get in touch with Norton for info on UK rights.

A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk

One of the first warts-and-all memoirs of motherhood. Cusk writes with righteous anger.

M(otherhood): On the choices of of being a woman by Pragya Agarwal

A powerful and urgent argument for the need to tackle society's obsession with women's bodies and fertility.

I’M LOVING:

Babies wearing sunglasses. You are welcome!

Realllllly enjoyed that, some new thinking for me as my wife and i don't have kids, but it shines a light on what i make and create in life and work and how invested i become in it... Thanks!