in which I stop trying to be good

leaving publishing + finding the work you feel compelled to do

Thanks to everyone who read Sunday’s Murmuration and shared their experiences of protest! Reassuring to know I’m in good company and that we have plenty of rebel-rousers in our midst.

Here’s the tl;dr version of today’s newsletter: I’m leaving my job as a commissioning editor at HarperCollins and becoming a freelance writer & editor. You can commission me to write or edit for you, or we can work on your book project together! Find out how here.

Sequestered in the bottom drawer of my desk are the tools of my trade: a Thinkpad laptop and a pair of noise-cancelling headphones. For the past six years I’ve lugged both around book fairs and meeting rooms looking for somewhere quiet enough to have an author call. I’ve spent countless hours chiselling away at manuscripts, using track changes to ask an author ‘is that what you really mean?’

In my personal inbox a pro forma email reminds me that All company property must be returned to the techdesk before your last day.

If I’m being honest, it’s a task I’ve been putting off. It seems to serve as the fullstop to a job I have mostly relished. I fell into publishing somewhat accidentally after getting a place on a graduate trainee programme. At the time I’d just left an organisation that didn’t seem to want me, and was looking for what might be the next right step. I spent the subsequent years getting to grips with editorial work and eventually became a commissioning editor for William Collins, HarperCollins’s literary nonfiction imprint.

Publishing wasn’t exactly a job I sought out with utter conviction, but once I was within it’s hallowed walls I realised that perhaps I could bring my own perspective to bear on my little corner of the industry. Over the years, commissioning books and working with authors is a job that I came to derive deep satisfaction from. I was privileged to give platforms to people and ideas which have traditionally been deprived of airtime, and help my authors identify which of their stories and arguments would be of benefit to a wider audience.

And yet.

And yet somewhere along the line I quietly came to realise that something wasn’t working.

The more that I gave myself to that work, the more distant I felt from myself. Initially I thought I just wasn’t working hard enough, so I worked harder, and harder, but the more I tried to force myself into the publishing mould of being the ‘perfect editor’ (peppy, smiling, working 60 hour weeks without breaking a sweat) the more forcefully I could feel myself withdrawing.

Have you ever experienced that? When your head and heart are totally at odds with each other? On paper I loved the idea of being an editor and wanted it to be my long-term career. Free books! Relationships with creative people! But another part of me, located somewhere around my gut, had other ideas. This part of me said things like ‘I think we should move to Somerset’ and ‘you should start writing a newsletter’. Neither of which are particularly conducive to a career at a central London publishing house.

Work hard and be a good girl

Work is a funny concept, when you think about it. Often our perception of what work is ‘for’ is deeply wedded to the environment we grew up in. Perhaps you grew up with a parent who worked in advertising or financial services; it would not be unreasonable for you to think that we work and find a job in order to be financially compensated for our time.

Growing up within a christian household, I imbibed a slightly different perspective. As a child I was exposed to the idea that work has an inherently moral element to it, and is one of the ways in which God works through us. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism the German sociologist Max Weber argued that puritanical (specifically Calvinist) religion had deeply influenced the development of capitalism, by making the theological idea of salvation by ‘works’ influential. The idea that we should work with a religious devotion and give our selves fully to our work is, perhaps surprisingly, a religious one.

I wasn’t given lectures on Weber’s theory at the family dinner table, but when I came to read his work at university I was struck by how much his writing resonated with my life. I grew up believing that God would ‘work’ through me, and more specifically, that there would be an obvious moralistic aspect to whatever job I pursued, even if it was a secular one. On a subconscious level, I think I believed that I could become ‘good’ if I just worked hard enough.

You do not have to be good

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting

In Wild Geese, the American poet Mary Oliver dismantles this idea. You do not have to be good, she says. You don’t have to ‘earn’ your salvation by working yourself to the bone.

I thought being an editor might be a way I could be ‘good’. I could infiltrate our toxic culture with brilliant writers and their wonderful books, and, in recognition of the hard work I’d done to achieve this, earn my salvation.

It’s a nice theory.

But I gradually came to realise the merely liking the idea of being a good editor was not enough. It was not enough to sustain the intensity of my workload or push me to go beyond my comfort zone. It was a job, and that’s ok! But anyone who works within commercial publishing will tell you that treating it ‘like a job’ is not really a long-term strategy for success.

If work is not about being good, in an ethical sense, then what is it about?

That, I think, is the question I have been grappling with for the past couple of years. Which leads us to the even stranger idea of having a ‘vocation’.

The thing you can’t not do

Translated from the latin term ‘vocatio’, meaning ‘a call or summons’, vocation was one of the concepts that influenced Weber’s writing on work. We see frequent references to it in the bible, whereby God calls people to do specific tasks or jobs (with varying degrees of success).

Take Jonah, who God called to preach to the people of Nineveh. Jonah rejects God’s call and boards a ship to Jaffa, only to promptly find himself thrown off the boat in the middle of a storm when the sailors on board realise that he is to blame for the turbulent weather. Cast adrift, Jonah is swallowed by a large sea creature, who eventually vomits him back up. Ignore your calling at your peril!

The Quaker educator and writer Parker Palmer describes the concept this way:

[A vocation] is something I can’t not do, for reasons I’m unable to explain to anyone else and don’t fully understand myself, but that are nonetheless compelling.

Vocation does not come from wilfulness. It comes from listening … I must listen to my life and try to understand what it is truly about—quite apart from what I would like it to be about—or my life will never represent anything real in the world, no matter.

Ouch. Sometimes it’s devastating to realise that the world you’ve built for yourself no longer feels right. When I was trying to explain to a friend how I felt about my work I said that I could feel my ‘soul deadening’. I no longer had new ideas, I no longer had the hunger or passion for new projects that had once got me out of bed in the morning. I stopped wanting to read proposals on my way home from work.

So was it all a waste of time? I don’t think so. Our vocations evolve, and I’m so glad to have spent a good chunk of my twenties at HarperCollins learning more about who I am. It’s a job that trained me to read, to edit and to think critically about the ideas shaping our world. It’s also job that put me in contact with many gifted authors whose books I had the privilege of editing. It is work that has helped me both grapple with and understand more fully what my vocation entails.

Mary Oliver offers her own answer to the question of what we do if we are not trying to be ‘good’.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

As I have listened to my life, it has become evident to me that the thing I can’t ‘not’ do is the very thing I’m doing now. I need to write. It is my way of being in the world. For too long I resisted acknowledging this, largely out of fear and shame. Fear of the vulnerability needed to do it, and shame that I would not be ‘good’ enough for it to sustain me.

But I no longer care about being good enough. I care more about living a life that is wholly my own, and which reflects more accurately the things I care deeply about. I care deeply about this planet, and about what we have done to it. I need to write about it, and put words to this moment of transition.

It is the only thing I think I can do.

Finding our vocation is about surrendering that fear and shame. It demands that we surrender the life we think we should lead, and instead more deeply become the people we already are.

OFFERINGS

Here are some more specifics about the kind of work I will be doing from now on:

Writing: I will be writing nonfiction essays, features and criticism examining our culture from a political and social perspective. I am also working on a novel.

Editing: I will be offering editorial services for writers and organisations.

For writers, artists and agencies: I will be offering 1:1 book development services; I will read your material and offer feedback on structure, style, plot and commercial potential.

For organisations and businesses: I will be offering editorial services. I am particularly keen to work with organisations or brands who have an environmental focus.

email: grace@gracepengelly.co.uk if you want to talk more. I’d love to work with you.

FIGURING OUT OUR VOCATION

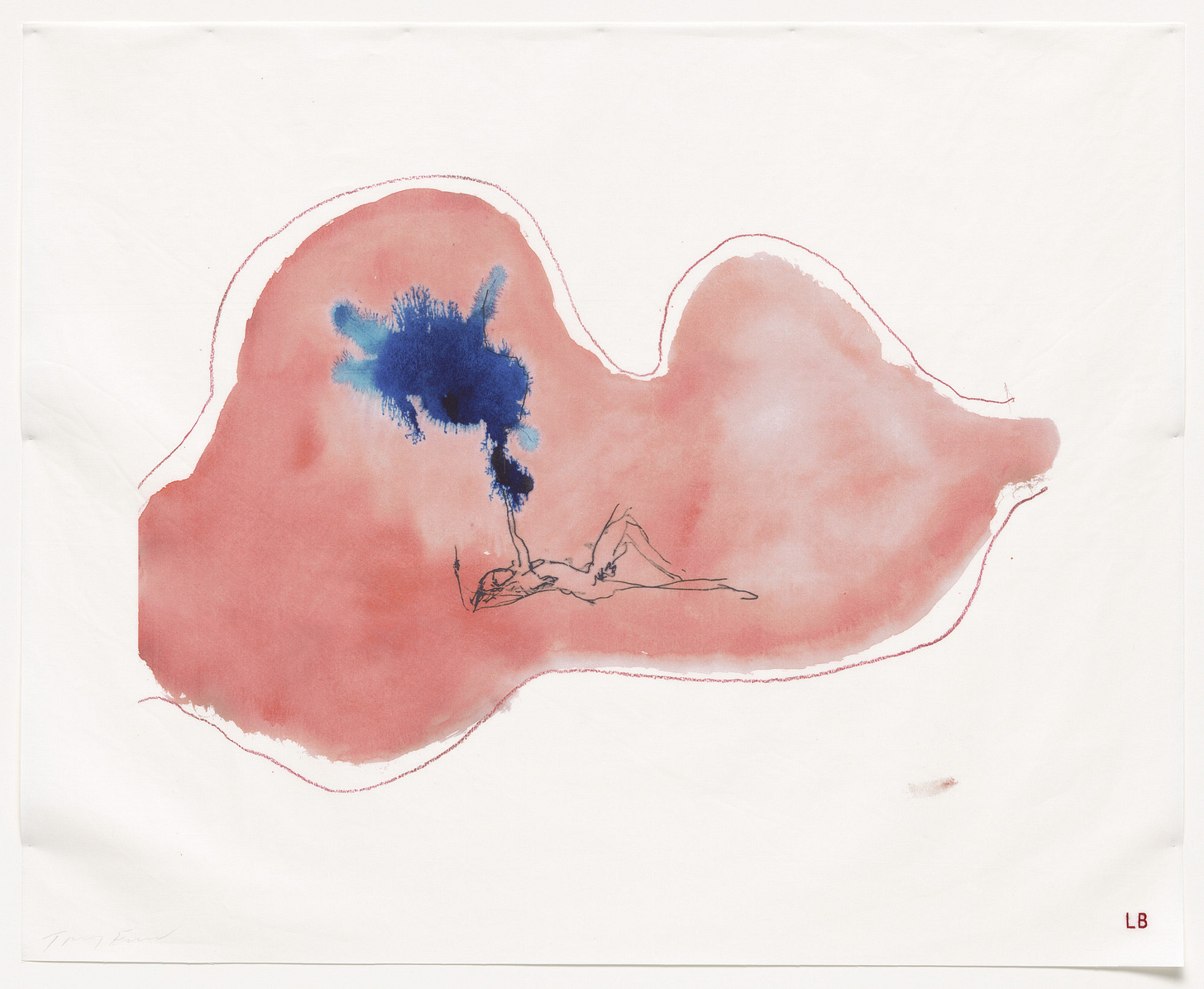

Tracey Emin on Louise Bourgeois: Women without Secrets

This is a wonderful documentary. Tracey reflects on her own art practice and how it intersects with that of the amazing female artist Louise Bourgeois, who only gained critical acclaim very late in her life.

Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation by Parker Palmer

I’ve returned to this book many times and always take away new insights. Parker writes with a deep sense of humility and grace. What a gift.

Rick Rubin on Magic, Everyday Mystery and Getting Creative, the OnBeing project

Krista Tippett does a great job of interviewing Rick here, helping him articulate the different ‘phases’ of creativity that he has come to observe as a music producer for the likes of Beastie Boys, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Johnny Cash.

Thanks for reading!

Grace

This is really helpful thank you.

Oh I totally relate to the ‘soul deadening’ comment… that’s why I had to leave PR in my early thirties and go on a massive soul quest which has lead me to where I am now… which I have accepted will always be evolving too! What an exciting time for you!