I’m not much of a gardener. It’s not that I don’t like gardens, but I’d much rather read about them, or admire other people’s, than actively look after my own. Thankfully my husband isn’t of the same disposition and likes nothing better than to spend a few hours tending to our patch. So this was how we spent this morning; I sat reading a book about gardens whilst my husband cleared out a bed of overgrown shrubbery.

I was reading Olivia Laing’s The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise, which documents her own journey of restoring a walled garden in Suffolk and considers the radical possibilities that they engender. For Laing, gardens are places of exclusion but also of ‘rebel outposts and communal dreams.’

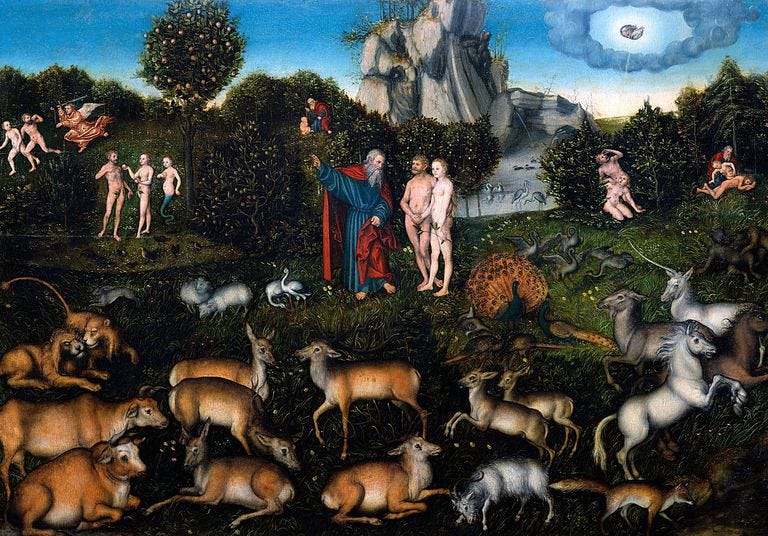

I was particularly struck by a section where Laing considers the epic poem Paradise Lost by John Milton, which depicts the fall of man and their subsequent exclusion from the garden of Eden, as described in the book of Genesis. Milton was writing as the resolute failure of his Republican side during the English Civil War was becoming apparent. This failure is mirrored in his epic work, which depicts Adam and Eve and Satan facing banishment from Eden and Heaven respectively. Eve, who had a ‘luminous collaboration’ with Eden, is devastated to realise that she must spend the remainder of her days ‘estranged and alienated’ from it, tending to the dry and desolate land which is now her home.

Our garden is just twenty-three miles from Stonehenge, the monument targeted by Just Stop Oil this week. A couple of protestors, one of whom is a 73 year old Quaker, sprayed orange corn-starch powder over the stones, prompting a predictably outraged response, both from the mainstream media and political establishment. Kier Starmer called them ‘pathetic’ whilst others, like archaeologist Mike Pitts, pointed out that ‘a rich garden of life has grown on the megaliths, an exceptional lichen garden has grown. So it’s potentially quite concerning’. At the other end of the spectrum,

suggested that Just Stop Oil are best understood as an art collective:Like a lot of artists they pretend they’re actually political activists, like a lot of artists they work by refashioning existing works, unlike a lot of artists, their stuff is actually visually interesting.

I suspect that Milton, who continued to write tracts about the republican cause well after it’s demise, would probably have plenty in common with the JSO protestors if he were alive today. It’s thought that whilst other ‘traytors’ were hung, drawn and quartered for their treason, Milton’s life was only spared thanks to the intervention of a friend. Given the febrile underbelly of British culture, it strikes me that JSO are fortunate to live in an era which has outlawed capital punishment.

So where does all this leave us? What has the orange cornstarch achieved? This, afterall, is one of the main criticisms of JSO and other protest movements. That their actions are fruitless, alienating the public from the climate cause which they so deeply care about. Well, I’m not sure that trying to make sense of JSO in ‘rational’ terms is particularly productive, and that’s because they do not perceive the world the way the majority of us seem to. For example, most of the public look at Stonehenge and see a precious cultural monument which has been carefully preserved for the benefit of future generations. JSO look at Stonehenge and then see the large road that runs straight past it, and the plans to build a tunnel directly underneath the site in order to increase traffic capacity. For this campaign group, the world is already a site of desecration, to suggest otherwise is to be blind to the damage that has already been caused by man’s wilful negligence. They are fighting for the future of the earth, but it is an earth which has already been fundamentally compromised, or ‘lost’.

In contrast to JSO’s dystopian vision, Laing argues that Paradise Lost:

imagines what it’s like to inhabit this state of failure and disillusionment … but it also considers how to proceed from it. It’s propelled by an almost intolerable need to understand what it means to have failed and what one ought to do once failure has occurred, both by imagining a process of future reparations and by re-envisaging the nature of an intact, untarnished world.

What separates JSO from Milton, then, is perhaps their propensity to ‘re-envision’ the world. Laing points out that Milton never stopped imagining the world as it might be. ‘He sat in that turbulent and fearful darkness and imagined the mother of all utopias, Eden, right down to how the air might have tasted. ‘A Wilderness of sweets … Wilde above Rule or Art.’

When we allow ourselves to fully acknowledge the darkness of the world in which we inhabit, imagining the world as it ‘could be’ feels almost impossible. But Milton shows us that it can be done. I think anyone who fears for the future must try, if at all possible, to engage in this work. I for one am glad we have writers like Olivia Laing to point us in the right direction.

Thank you for reading, Golden People.

If you enjoyed this, then you might appreciate this article about the Fossil Free Books campaign, and this piece about the pop-art Nun Corita Kent.

The Murmuration is a bi-weekly newsletter written by me, Grace Pengelly, which aims to dig beneath the topsoil of everyday life. It is fully funded by paid-supporters, whose contributions enable me to give it the love and attention it deserves. I recently lowered the price of monthly and annual subscriptions to make them more affordable for everyone, but will only be able to keep it at this lower price point if a few of you sign up!

Find out how to upgrade your subscription below. (Thank you in advance)

Dear Friend, while I appreciate the depth of your thinking. I do wonder whether you inquired as to the possible presence of a Buddhist a Jaine or representative from any other group who publicly show care for our planet. The Quaker may well have stood out uncomfortably in your opinion, and makes me sad, though please think on this question.