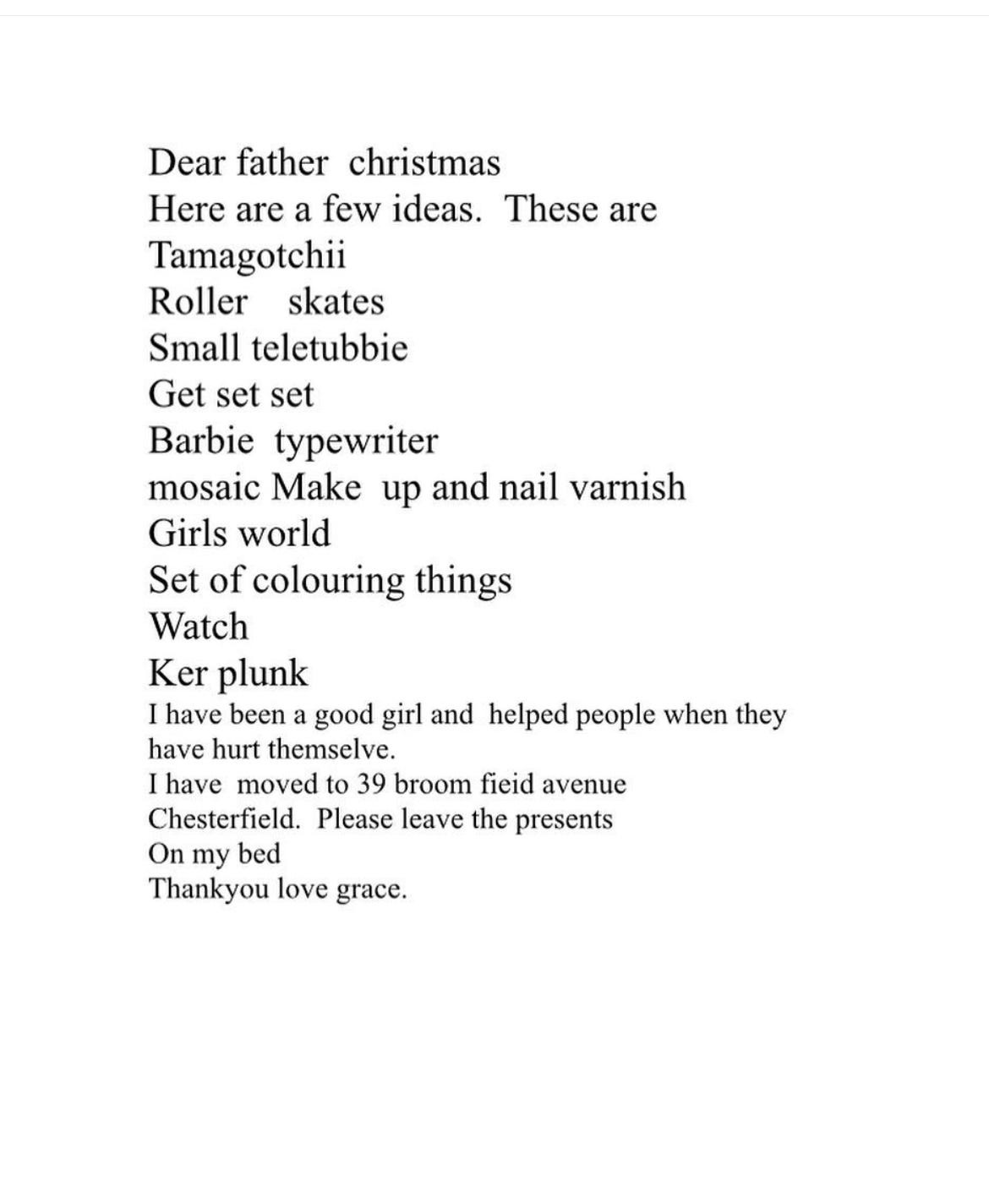

I’m a digital native – which means that, unlike my parents, I cannot remember a world which predates the internet. In some of my earliest memories I’m perched on my dads lap, clumsily tapping out a letter to Father Christmas (which he saved for posterity – see below), or designing a mother’s day card on Sierra Print Artist (above), a very early graphic design programme that occupied a similar role to the one Canva does today.

Perhaps unusually for a farmer-turned-Reverend hailing from North Devon, Dad has always been fascinated by the systems that computers operate on. During the course of my childhood he became an early adopter and advocate of open-source operating systems (OS), like Linux’s Ubuntu. Unlike Microsoft or Apple’s licensed operating systems the Linux OS has always been available for free, with a new version released roughly every two years. Dad loved the vision behind the project, and would evangelise about the possibilities of it to his teenage daughters, and pretty much anyone else who would listen1. Needless to say, his enthusiasm was not exactly reciprocated by his offspring, who would much rather have the operating system which everyone else was using, duh.

In the South African languages from which the word ‘Ubuntu’ originates, the term roughly translates to ‘I am because we are’. Mark Shuttleworth, the South African founder and CEO of Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu, chose it because ‘it’s not a technology name – it’s a name about people so as a community we tend to attract people who care about society, care about the way technology is used and the changes that technology can create’

When I think about the way Linux captured my Dad’s imagination, I think Mark Shuttleworth’s description feels pretty spot on, and it seems clear that this era of computing and technology development was one driven by possibility and a sense of excitement about what might be achieved in service of humanity. Shuttleworth seemed to confirm this sentiment in a recent interview, saying that ‘The internet was fundamentally about connecting people together and it led to just extraordinary shifts in what people could organize and how you could organize businesses and nonprofits. The internet allowed us to harness our minds in a fundamentally different way.’

I like the slightly different translation of Ubuntu used by Sotho-Tswana, Zulu and Xhosa tribes ‘A person is a person through people’. It speaks to the fact that we exist because our mother gave birth to us – but also that our continued existence is dependent on humanity too. Everything that we need to survive is provided by the people we exist in community with. Of course - these ideas are expressed in many societies. In British culture, we could argue that John Donne’s poem ‘No Man is an Island’ articulates a very similar philosophy to that of Ubuntu:

No man is an island,

Entire of itself;

Every man is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main.

In its early days, OpenAI seemed to share some of the ideals expressed by the likes of Mark Shuttleworth. In it’s founding charter, it’s mission was ‘to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity’. But in 2019 OpenAI moved from a non-profit to a ‘capped’ for profit and announced that it would commercially license its technologies. It seemed to mark a shift away from the original vision of OpenAI, which was further underscored by the decision not to make their source code openly available for review. The founders of OpenAI would latterly defend this decision, arguing that safety is the reason not to share source code – ‘if a hard takeoff occurs, and a safe AI is harder to build than an unsafe one, then by opensourcing everything, we make it easy for someone unscrupulous with access to overwhelming amount of hardware to build an unsafe AI, which will experience a hard takeoff.’

The discourse around the rapid growth of AI systems has felt inescapable for months now. Like you, I’m surrounded by people who hold varying feelings about it. My husband – an environmental engineer who designs computer systems – feels that the narrative and hype surrounding it has become overblown. ‘A few years ago it was big data – this is just the next faddy thing that people want to sell’. He has built AI systems which are already being used in buildings, and remains fairly cynical about the level of sophistication current AI platforms are offering, pointing out that there is a huge difference between hyping AI and actually deploying AI tools that work effectively. By contrast, a friend of mine who returned to work after having a baby described feeling like she had ‘missed an industrial revolution’, her work as a qualitative researcher for a think tank(!) looks set to fundamentally change now that chatGPT can produce in seconds reports which once took her days days to write.

As a writer my primary concerns about AI relate to the impact it will have upon human creativity, democracy and our capacity for critical thought. Had this technological development taken place in a different political moment, perhaps I would feel differently. But surely it’s obvious that the political environment which AI is being launched into is a recipe for disaster. As the founders of OpenAI point out themselves, it’s ‘unscrupulous’ actors - and we’re not short of those right now - which pose a very real threat if AI crosses the threshold of general intelligence.

To state the obvious: we are not being led by wise people who are willing to prioritise the broader interests of democracy. In the face of genocide and fascist politics in the states, the democratic and human rights norms which our political systems have spent decades trying to develop and uphold have been utterly disregarded by the West in favour of cold political realism and self-interest. In the UK, not even a former human rights lawyer-turned Prime Minister seems inclined to stop sending arms to Israel: so what hope do we have when it comes to AI?

The mood music from Labour has been depressing. As with Israel, Labour is acting as if it has no choice but to satisfy every demand of the AI lobby. Under pressure to appease data-hungry AI developers, the government has signalled that it will relax copyright rules which would theoretically prevent the scraping of IP (like novels, millions of which have already been scraped in order to train language models).

My other major worry relates to the diminishment of our critical capacities at a time when we need them more than ever. It feels ridiculous to even have to point this out, but every time we use language learning models (LLM) we are making a choice to not do a particular type of thinking for ourselves. In a recent MIT study, compared to a ‘search-engine only’ group and a ‘brain-only’ group, ChatGPT users were found to have the lowest brain engagement when writing an essay and ‘consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioural levels.’ In other words, using LLM weakens our cognitive function.

So once again I’m left wondering: where are the people who have a clear vision for the future of society which is grounded in wisdom and long-termism? Where are the people who are willing to say the things that might seem unpopular, but which put the interests of the majority above a minority of powerful billionaires? And why does Labour seem so uninterested in offering moral clarity on anything? The mind truly boggles!

Towards the end of the same interview I linked to above, Mark Shuttleworth is asked about AI and suggests that the birth of AI should not be thought about in the same way as the dawn of the internet. ‘AI is something of a threat to certain kinds of tasks and functions’ he pointed out, ‘the kind of Western consensus capitalism view of the world is an era - everything is an era, right? So then the question is how else might we organise ourselves? And when might it become optimal to move to a different way of organising ourselves…We should be open to the idea that there are other ways to organise ourselves.’

This feels like a far more fertile and interesting line of thinking for us to explore. Shuttleworth is encouraging us not to simply engage with AI in the way that capitalism wants and needs us to. If it frees up our time by making us more productive, then how are governments going to navigate large parts of a ‘workforce’ which perhaps only needs to work three or four days a week? Could we fundamentally redesign the way we understand the economic ‘value’ of humans? Surely these are the urgent questions which we need to be giving our time and attention to.

Thank you for reading!

If you value these essays, then do consider becoming a paid-supporter of The Murmuration, a newsletter which tries to think through some of these big questions in real time. You can support my work from just £3 a month through an annual subscription.

And don’t forget to join us for the inaugural BRAVE NEW WORLDS Book Club next Thursday, 26th April. Get your (free) tickets here.

He also owns numerous articles of Ubuntu-branded clothing!

Thank you for saying this. I find the whole thing deeply alarming, so it's encouraging that the push-back seems to be growing. It's always slightly depressing though when we need these scientific studies to point out something that ought to be obvious. 'LLMs make us stupid' falls into the same category as 'Exercise turns out to be good for our health'. Decreasing resistance increases atrophy; what is neglected withers; so of course delegating thought and problem solving and creativity is going to reduce our capacity to think and problem solve and be creative. And as you say, we need those things more than ever.