When I avoid talking about God

She turns up anyway.

Medium-term readers of this newsletter will know that I’m often writing around the edges of God, Yahweh, the transcendent, or whatever word you use to describe the divine. The subjects I cover tend to have a spiritual theme or perspective, but I’m always wary of making them too religious, lest prospective readers write me off as ‘woo woo’ or mentally deranged. (I’m definitely mentally deranged, but that’s another story for another time).

I feel nervous talking about God largely because I’m British, and in the UK discussion of religious belief is typically greeted with a collective eye-roll by the media, as if it’s some quaint artifact of a bygone era.

Why so?

Well, I’d attribute it in part to a disconnect between the British media and the reality of the our spiritual identity, which I would argue is broadly agnostic, as opposed to atheistic.

In this regard, Alastair Campbell is often (wrongly) identified as ushering in an atheistic age thanks to his ‘we don’t do God’ edict, which was his reply when Tony Blair asked him about his faith. Today this anecdote is offered, along with statistics about declining church attendance and the rise of the ‘nons1’, as a priori evidence of Britain’s secular shift. But they are the effects of cultural change, rather than their cause.

Agnosticism suffers from some of the same problems that plague other beliefs. Although resistant to dogma, agnosticism is delightfully vague and open to interpretation; a spiritual shrug of sorts. Hardly a sexy angle for the UK’s media, which chooses instead to tell stories about institutional free-fall and religious extremism.

These days I find the debate around whether the UK is getting less religious quite dull. It’s just the same stories and retorts hashed out again and again and we don’t ever seem to gain much latitude on what’s really going on in people’s minds, never mind their souls. This discussion also tends to also focus on religion (with a capital R) as opposed to God. Religion comes with institutions, buildings, rules and people we can dismiss and critique. God, meanwhile, is everywhere and nowhere, a tricky entity to pin down.

My suspicion is that British people want to talk about God, but don’t know how, so we talk about religion instead. I say this because in almost every friendship I’ve ever had there comes a point where the prospective friend, having picked up on some cues, will pluck up the courage to ask me if I’m religious.

Here’s how that conversation usually goes:

‘Are you religious then?’ -nervous smile-

‘Yes, I suppose I am.’

‘Oh, why’s that?’

-queue my stock explanation of a Christian upbringing, being the daughter of Reverend, explaining that I don’t believe homosexuality is a sin etc etc-

But underneath this question is a genuine curiosity about theism, which finds itself denied, funnelled instead into a somewhat circular, hollowed-out discourse about religion. And my response to that curiosity also denies them real information about my beliefs, because instead of talking about God, I talk around the edges of the divine. In defence mode I offer my off-the-bat rejections of things commonly associated with Christianity-as-Religion (sexism, homophobia, anti-environmentalism), instead of leaning into the less tangible but more numinous reality of my experiences.

This matters because it impoverishes our relationships to each other. Instead of offering our whole selves, we present a sanitised version of our true being, made palatable for whoever our audience is in that moment. I do this all the time, fearing that I won’t be taken seriously if I’m honest about who I am. So I try my best to avoid talking about God, and if I do, it’s in guarded terms.

I’ve become so sensitive to the prejudices and reservations others have about my religion, that my ability to communicate the true nature of my relationship with God has been altered, diminished, perhaps even hidden itself under a bushel …

As a teenager I had a less complicated relationship with my faith. So much so that I would print out quotations that spoke to me and stick them up in my bedroom wall. I wasn’t worried about being dismissed as earnest or homophobic back then. One writer that helped me in this period of my life was C.S Lewis, author of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Mere Christianity. In cursive text I’d printed out the following passage from a lecture he gave to The Oxford Socratic Club:

I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.

Walking into my dad’s study the other day I was surprised to see the quote -on the same bit of paper- to his notice board. It reminded me of the simplicity with which I sought out God at that time.

God didn’t have to defend herself to me or be obliquely woven into my essays in case people figured out she was there.

She was there as the Sun had risen.

And she’s still here, almost fifteen years on.

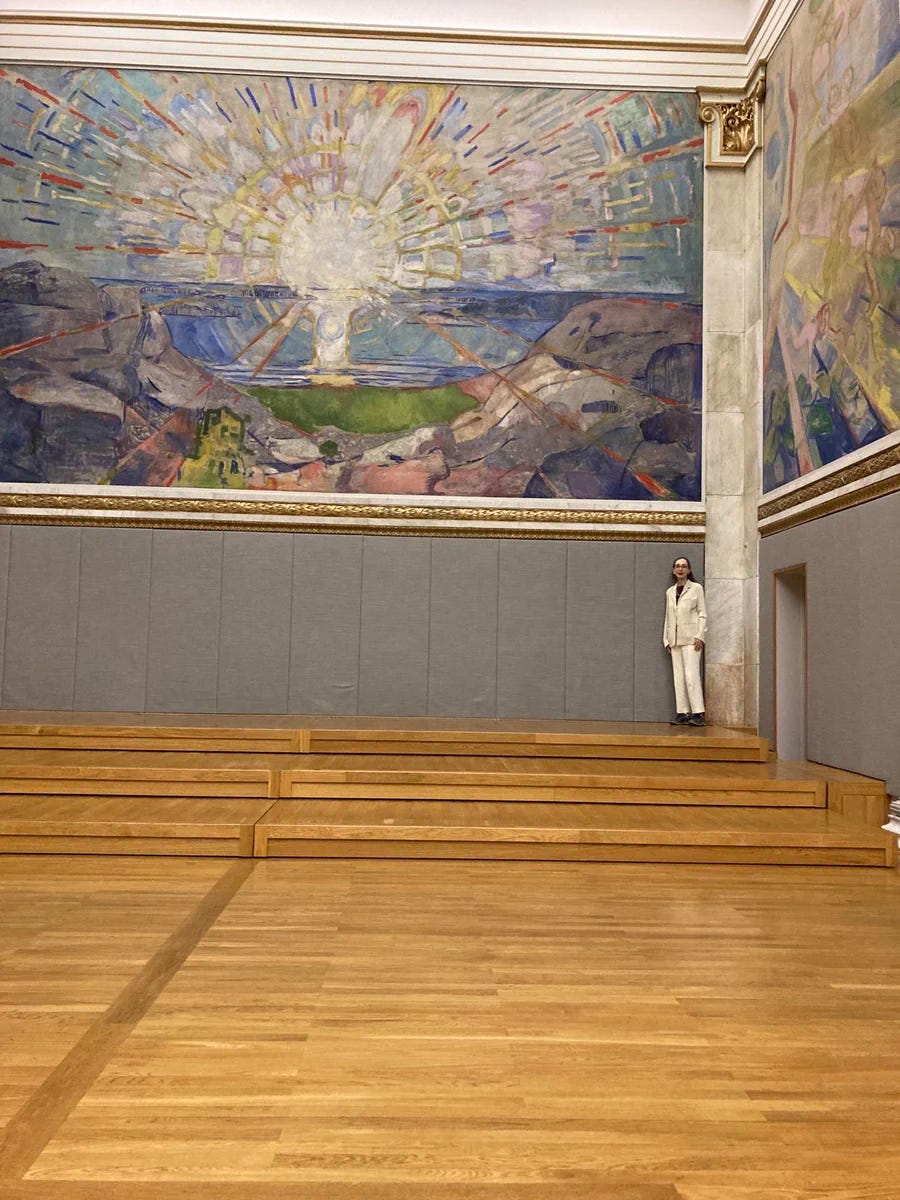

Post-script: shortly after sharing this newsletter the novelist Joyce Carol Oates shared this picture of herself ‘admiring Munch’s monumental mural at the University of Oslo on Twitter. It’s name …?

Thanks for reading. I’d love to know what you think about God in the comments.

HEAVENLY RECOMMENDATIONS

BOOK: Theology for the End of the World by Marika Rose

What if our desire to save the world is part of the problem asks Marika, in this highly provocative and whip-smart critique of apocalyptic theologies.

FILM: “Insert Complicated Title Here” by Virgil Abloh

Virgil Abloh was a creative powerhouse, most well known for his fashion brand Off-White, and for his direction of Louis Vuitton. In this lecture given at Harvard’s School of Design, Virgil unpacks his design philosophies in a typically inventive and illuminating way.

MUSIC: The Hardest Part by Olivia Dean ft. Leon Bridges

This is just divine!! *chefs kiss*

PLUS: I will be in conversation with the writer Luke Turner at Greenbelt Festival on Friday 25th August. We’ll be talking about his brilliant memoir ‘Out of the Woods’ at a talk called ‘In the Beginning, God Made Bisexuals’. Catch us at the Treehouse at 1.30pm! I’d love to see you there.

It’s such a hard subject to talk about outside a faith context. You have to grapple with all the (mostly) negative perceptions people have about believers. Then I see how some people of faith behave publicly and I cringe. I grappled with it hard when I became a Christian in my thirties from an entirely atheist position and background. Through grappling cane freedom. Stay courageous Grace!

Thank you for sharing Grace. I too did not talk about God much when I was in school. I think I asked my friends once if they were Christian and they claimed to be just because their parents or grandparents claimed to be Christian. They had never set foot in a church or read a bible and did not in any way have a relationship with God. I feel there are a lot of people in England who claim to be Christian just because England is said to be a Christian nation, as though Christianity is by birth just like nationality.

Personally, I grew up in a Christian family. During my time in England I went to a small church and became part of that church’s community in Worksop. However, because my friends didn’t believe in God, my relationship with God was luke-warm and I would go to church just to tick the register (religion). At this point in my life, my relationship with God through Jesus Christ is at the best it has ever been and he is everything to me, my creator, father, friend, comfort, deliverer, the list goes on.