marriage and its discontents

on humans and their messy unions

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to talk about marriage. Happy marriages, unhappy marriages and everything scattered in-between. Before we dive in, I should probably state some preliminary facts. For all intents and purposes, I am a ‘young married’, which means that I walked down the aisle before I was old enough to feel any anxiety or qualms about the mammoth thing I was entering into. Most days I view this as a good thing.

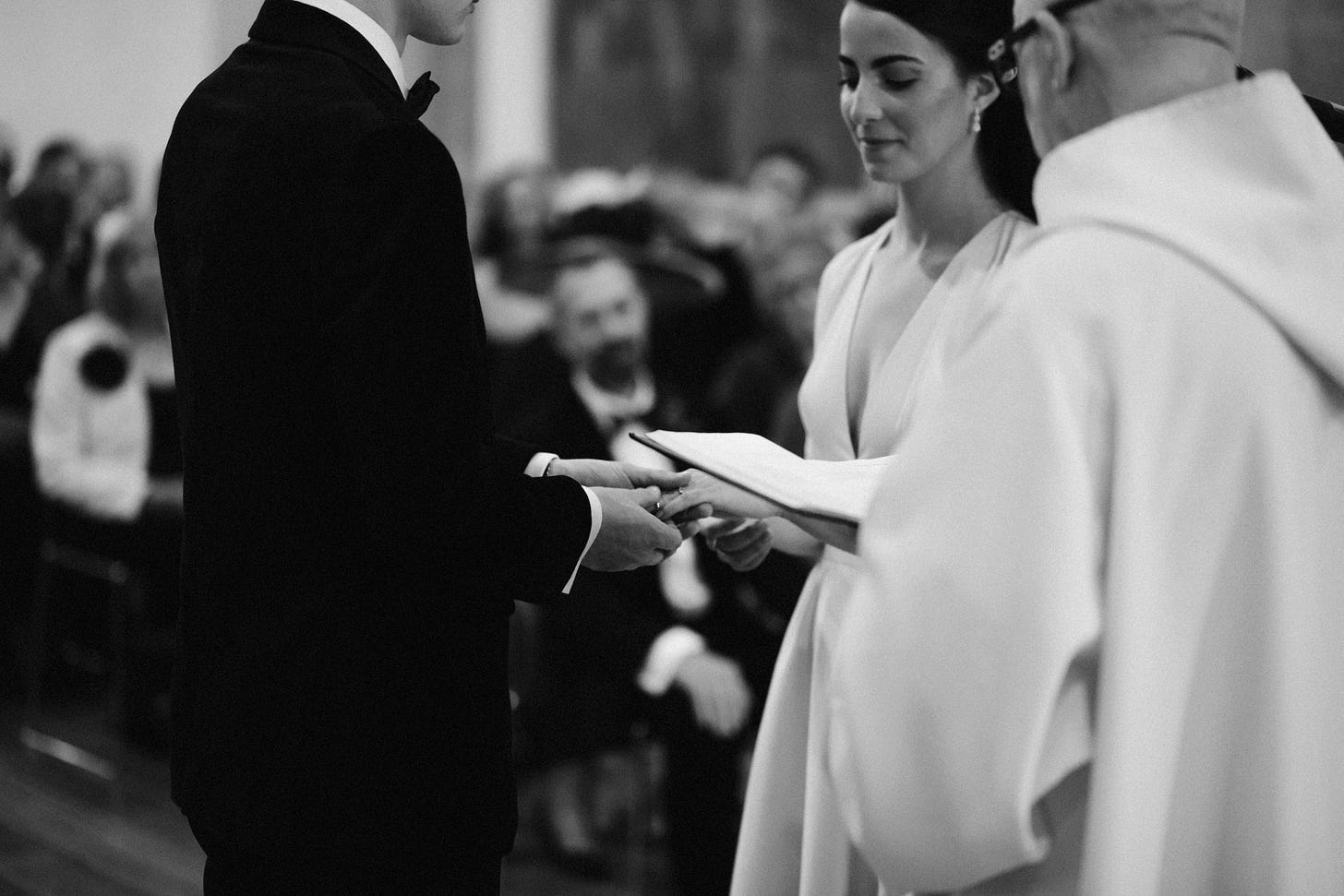

I was twenty-three and my then boyfriend was twenty-four. We had both been raised in Christian families, so getting married shortly before we bought a house together seemed like a pretty normal thing to do. Neither of us were children of divorce, nor had we really witnessed many divorces unfold around us. It is only as we’ve grown older that I realised just how mad unusual getting married in your early twenties is. We’ve now been married for seven years.

Anyway, I digress. I wanted to write about marriage after watching Anatomy of a Fall (2023), a film about a writer called Sandra Voyter who is suspected of murdering her husband, Samuel. In the film, we witness the couple’s son take his dog for a walk. Upon his return, his father is found dead at the foot of their chalet in an apparent fall, his blood soaking into the snow. The only other person in the house during this period was Sandra. Did he jump or was he pushed? seems to be the mystery viewers are tasked with solving from this point on. Defence and prosecution teams gather their evidence, and the couple’s son is tasked with testifying in a case which could send his mother to prison for his father’s murder.

As the court case progresses, supposedly shocking revelations emerge. The couple, who were both writers, sometimes fought(!) and Samuel felt deeply frustrated by his childcare responsibilities, which he felt deprived him of the writing time his wife seemed to have in abundance. The day before his death the couple had a major fight, which Samuel recorded on his phone. The recording is played and the prosecution have a field day. Samuel’s therapist also testifies that he was deeply unhappy in his relationship to Sandra and had been on anti-depressants to improve his mood.

A picture emerges of a competitive couple in a fractious marriage, which had often been loving, but ultimately appeared to sink under the weight of contradictory desires, and perhaps contradictory understandings of what a modern ‘marriage’ entails. At one point, frustrated by the prosecution’s attempt to read her fiction as memoir, Sandra interjects:

‘I don't know, you, you come here, okay, with your, maybe your opinion, and you tell me who Samuel was, and what we were going through... But what you say is just a... it is just... a little part of the whole situation, you know? I mean, sometimes... Sometimes a couple is kind of a chaos. And everybody is lost. No? And sometimes we fight together and sometimes we fight alone and sometimes we fight against each other, that happens, and I think it's possible that Samuel needed to see things the way you describe them, but... if- if I'd been seeing a therapist, he could stand here too and say very ugly things about Samuel. But would those things be true?’

Sometimes a couple is a kind of chaos. This struck me as a true statement, a statement which would probably resonate with anyone who has been in a long-term relationship. The fact of our love for each other does not eradicate the enormous challenges which life presents. Nor does the presence of conflict or chaos necessarily mean that a marriage is no longer loving. A marriage is not a static thing which remains consistent day-to-day, and that’s because it’s a partnership entered into by humans; those most inconsistent and mysterious of creatures.

But so often this nuanced reality jars with our cultural expectations of marriage, which demands that couples present only the sanitised, picture-perfect version of their relationship, lest it be ruinous to one of the individuals concerned. In an essay recently published in The Cut, the novelist Emily Gould described how close she came to divorcing her husband during a period in which she was mentally unwell, and ultimately diagnosed with bi-polar disorder. Here, she describes a divorce mediation session:

I was the one who talked the most in that session, blaming Keith for making me go crazy, even though I knew this wasn’t technically true or possible: I had gone crazy from a combination of sky-high stress and a too-high SSRI prescription and a latent crazy that had been in me, part of me, since long before Keith married me, since I was born. Still, I blamed his job, his book, his ambition and workaholism, which always surpassed my own efforts.

The parallels between Gould’s experience and those depicted in Anatomy of a Fall are almost uncanny (barring murder). In both narratives, two pairs of married writers struggle with their competing ambition and varying levels of success. And in both cases, one writer accuses the other of effectively cannibalising ‘their’ biography or story in an unethical manner. Reflecting on her husband’s memoir, Gould says that ‘The opening chapter described my giving birth to our first son, and I didn’t realize how violated I felt by that until it was vetted by The New Yorker’s fact-checker after that section was selected as an excerpt for its website. Had a geyser of blood shot out of my vagina? I didn’t actually know.’

The question of how domestic labour is allocated contributes to feelings of resentment and frustration within these relationships. Gould describes how she assumed a domestic role after the birth of their child : ‘At first, I did all the cooking because I liked cooking and then, when I stopped liking cooking, I did it anyway out of habit.’ In Anatomy of a Fall, it is the husband Samuel who claims to do the majority of the housework and childcare, subverting traditional gender roles and making the audience question if Sandra does her ‘fair share’. Halfway through the fight which is recorded and played to the court, Sandra is heard declaring that she doesn’t ‘believe in the notion of reciprocity in a couple. It's naive and, frankly, it's depressing.'

In many ways Sandra’s husband Samuel appears to be playing ‘the woman’ within their relationship. As I watched him moan about cooking meals and homeschooling his son, I couldn’t help but wonder if the ‘unfair’ level of domestic work he was complaining about was in fact just a closer approximation of what domestic parity might look like in a marriage.

I was staggered by the public reaction to Gould’s essay, which dominated the ‘discourse’ on X for a good week after it was published. Here’s a selection:

Gould’s transparency and honesty about their relationship is depicted in many of these tweets as insult to her husband, (who notably read the essay, offering few notes). More specifically, radical honesty about marriage, as provided by both Gould and Sandra Voyter’s character, seems to fundamentally subvert the role that married women are expected to perform for society. In this role, we must not ‘bring shame’ upon our husbands by detailing the reality of our marriages. To provide genuine insight into a marriage’s terrain is instead interpreted in both cases as a denigrating, emasculating act, which serves to humiliate their (male) partner’s. If things are difficult, it is better to put up with it and suffer in silence than air your dirty laundry (which you should have cleaned by now) in public.

I think these dynamics are very much at play in our society. We see it in the way that divorce is so often hushed up or left unreferenced. The perceived ‘failure’ of that couple to perform the ‘happy marriage’ becomes instead a source of shame and unhappiness. Technology now enables us to expunge these ‘failed’ relationships from our feeds and profiles in the click of a button, so we can pretend they didn’t happen. But perhaps we should instead view divorce as another form of radical honesty, in which the couple have concluded that the reality or truth of their relationship is no longer tenable.

Rates of marriage are in sharp decline in the West. In the UK, compared to 1991, adults in 2021 were 44% more likely to never have been married. But is it really any wonder? When a marriage is so often treated as a binary success or failure? And when those who dare to speak candidly about marriage are castigated as transgressors?

Increasingly, I am inclined to think of marriage as a container. It is not an end-point or a vision of heavenly perfection made mortal, but a sort of spiritual container in which two people commit to do life together. Humans are messy, and so the unions we enter into are messy, too. Sometimes a marriage will no longer be the appropriate medium for a couple, because their lives have fundamentally diverged. And that’s sad, but it’s also ok. What’s not ok is our seeming inability to portray marriage in a truthful way, in a way that shows it’s ups and downs and still says: we’re committed to each other not because we are perfect but because we are fallible.

To my mind this is a more holy understanding of marriage, because at its heart it’s about forgiveness, togetherness and love. It’s not about perfection - it’s instead an acknowledgement and radical acceptance of ‘sin’ - whatever that might mean for you. For me, it means finding neutral ground after another fight. It means finding the language to apologise if (when) I fuck up. This is the kind of love which ‘does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.’ This is the kind of love I see reflected in Gould’s essay and her marriage. It’s more capacious, imaginative, and resilient.

I do feel that there is the potential for marriage to be reimagined for the 21st century, for it to cleave itself from the unrealistic, patriarchal demands which the generations before us often tried and failed to meet. For it to be less performative and more honest. More, dare I say it, truthful.

Thanks for reading.

I’m so glad that new readers are joining our number. Welcome, welcome. Do say hello in the comments or drop me an email. The Murmuration is an essay-based newsletter that goes out twice a month. Paid subscribers also receive GOLDEN HOUR on Sundays, which has recently featured field notes from a trip to a Quaker meeting, some thoughts on the Super Bowl and Gaza, and a feminist defence of Poor Things.

RECCOMENDATION CORNER

If you haven’t read Pankaj Mishra’s phenomenal essay ‘The Shoah After Gaza’ in this month’s LRB, then please set aside some time to read it. It’s some of the most thoughtful writing on Israel/Palestine I’ve come across.

The oft-mention poet Harry Baker is now a Substacker (yes I’m taking credit). Harry writes about the weird and wonderful aspects of life and his newsletters are predictably joyful. Give him a follow or a subscribe.

I loved reading Haley Nahman ‘s first piece since having a baby ‘Like a mother’ ‘Becoming a mother is the hardest thing I’ve done by far, and still it’s no match for the giddiness that gallops through my body when Sunny laughs, as if the bell just rang on the last day of school. It’s no match, even, for the brown tufts of hair that curl around her ears, or the way her starfish hands wander gently around my neck, exploring her new world. I’m lost, found, bleeding, home. I’m leaning over her bassinet to make sure she’s sleeping, but she’s grinning at me, and I’m grinning back.’

On the subject of motherhood, I’ll soon be paying a visit to the Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood exhibition at the Arnolfini in Bristol. Some of my all time fav. babes are showing, inc: Tracey Emin, Chantal Joffe, Bobby Baker and Caroline Walker.

If you enjoyed reading today’s essay, then please restack, hit the heart or leave a comment. <3

More people are writing about the reality of motherhood, I wonder if more will be written about the reality of marriage? In recent conversations here on Substack writers have discussed the issues of how much to expose other people's lives and the perils of memoir. It seems these issues of consent, exposure and speaking our story would be issues in talking about marriage more openly too. I can see the potential for talking about marriage to bot wound a marriage further and to heal it depending on how it is done. Tricky areas to navigate but important.

Thanks for the pointer to Pankaj Mishra’s piece. Heavy going, but thought provoking. Like many people, I think, I started out feeling some sympathy with Israel's reaction to the Hamas attack (particularly because I have a personal connexion to one of the kibbutz targetted), but there is little doubt that things have now gone way too far. PM's analysis is very enlightening - and also frightening!